A debate on theatre criticism and its crisis in the UK

Crisis, what crisis?

by Andrew Haydon

London, October 24th 2013. Recently in Britain there has been a lot of talk about "A Crisis in Theatre Criticism". There are a number of reasons for this. It is well known that the newspaper industry is facing severe financial difficulties. Every newspaper has been forced to make staff redundant and cut the wages of the remaining workers. At the same time, journalists have been expected to do more work across an increasing number of platforms thanks to the expansion of online technologies. Until recently, this had only impacted on theatre criticism with reduced salaries, reduced coverage, and reduced opportunities for new writers and freelancers hoping to get a foot in the door of the profession. But now, with the announcement that the Independent on Sunday had fired all its critics and replaced their reviews with a chunk of the review from their daily sister title, lines from other papers' reviews and comments from Twitter, some people have started panicking.

There are reasons not to regard the Independent on Sunday as an example of things to come, however: its relevance among British newspapers is limited, its readership small and its website all but un-navigable. It has been in severe financial difficulties for a long time, so these cutbacks do not come as a surprise and there doesn't seem any question that other papers have the slightest intention of letting their critics go.

British theatre criticism has always been conducted in newspapers

Still, the situation with newspapers in the UK is uncomfortable. When I met my colleague Alexander Menden, who reports on culture in London for Süddeutsche Zeitung, and discovered he was only one of four correspondents in London for that paper alone; well, I couldn't help feeling that the Guardian having only one permanent member of staff in Berlin – responsible for covering politics, culture, sport, and also, bizarrely, Turkey – spoke volumes about the respective newspaper cultures in our two countries.

To understand why newspapers are so important to this debate on criticism in Britain, and why changes to print media here have a greater impact on theatre criticism than they might in Germany, it is crucial to understand that, with precious few exceptions, the entirety of British theatre criticism has been conducted in newspapers. There was a magazine, Plays and Players, in the late sixties until the late seventies; and current affairs magazines like The Spectator and The New Statesman do all still publish occasional theatre reviews, but until about 2007, when theatre-blogs appeared on the internet, if you talked about theatre criticism in Britain, you were basically talking about newspapers. There is no Theater der Zeit, no Theater Heute, and still, even now, no equivalent of nachtkritik.de. Although our closest near-relation, Exeunt, goes from strength to strength, and once it solves its internal organisational/editorial issues and secures a proper revenue stream, then it will likely mark a real renaissance in theatre coverage for the UK (at present Exeunt receives a small amount of money from advertising, but cannot, at present, afford to pay contributors).

From "Postdramatic Theatre" to ice cream in the West End

What is interesting is that this "crisis" coincides with the largest, fastest growth in theatre criticism since the advent of low-cost listings magazines like Time Out (1968-) and City Limits (1981-1993). (Although Time Out's theatre coverage has also been drastically scaled-back in the past two years.) With the sudden availability of free online self-publishing, theatre-blogging rapidly became an enormous growth industry (for some examples see the blogroll below).

Early adopter – the Theatre Blog of the Guardian

Early adopter – the Theatre Blog of the Guardian

was already set up in 2006.These blogs, in large part written without financial reward, were initially treated as suspect by a majority of the established newspaper critics, giving rise to many entirely specious "Bloggers vs Critics" pieces. As early as 2007, Michael Billington wrote an entirely nonsensical, contradictory argument claiming that blogs are: "more like an informal letter: a review," he argued "if it's to have any impact, has to have a definable structure. The critic, unlike the blogger, also has a duty to set any play or performance in its historical context." Ironicially, he wrote this piece for the Guardian's own "Theatre Blog".

As early as 2006, the Guardian had realised that the future of journalism lay in online expansion, and set up a number of more informal, comment-friendly blogs – including one for theatre. And, for a while, it invited the best writers who were already writing theatre blogs to write short pieces discussing diverse current issues in British Theatre – from the first mainstream British attention paid to Hans Thies-Lehmann's book "Postdramatic Theatre" to light meditations on the price and quality of ice cream in the West End. In 2011/12 the money ran out, and now it is written more-or-less solely by the (still excellent) staff-critic Lyn Gardner.

Crisis of taste – dead, white, males

By the way, prior to the rise of blogging, British theatre criticism was already facing an entirely different so-called "crisis": a crisis of taste and of representation. Put simply, most of the "chief" critics were old, white, male, and frequently exhibited deeply conservative tastes. As a result, some of the best work being made or shown in Britain was never being reviewed favourably. Which in turn caused real problems for forward-looking theatre managements trying to programme their theatres, or for companies who wanted to write texts outside of a 1960s kitchen sink-style or play classics with anything less than complete reverence for the written word. It is not surprising that so little German work – characterised as excessively "experimental", was seen in Britain.

As a result of the growth in blogs and independent theatre-reviewing websites, this stranglehold of half-a-dozen "dead, white, males" (the term for them coined by National Theatre director Nicholas Hytner) was broken. While Michael Billington might have objected to them, the Guardian's other main critic, Lyn Gardner, was an enthusiastic advocate; frequently giving advice, advancing the cause and careers of bloggers, and was instrumental in getting the best writers work writing for the Guardian, which in turn raised their profiles enough to make their own blogs far more cultural currency. However, this quiet revolution happened gradually between 2007 and 2012, during which time the print media also began to feel the pinch of both the global economic downturn and the continued mass exodus from newspaper-buying.

Shorter reviews, star-ratings – what's the future?

The question in Britain now, the current "crisis", is essentially this: if serious criticism in newspapers is finished – and there are many who would argue that with short reviews of only 350 words and a requirement to give each performance a "star-rating", it already was – where is it going to exist now? And how is anyone actually going to get paid for writing it?

The recently reported piece by the young digital-evangelist and blogger Jake Orr (and the many, many similar pieces by Mark Shenton at The Stage) strike me as a curious mixture of accurate concern, worst-case scenario-ising, and old-fashioned deference to print-journalism. Orr points out how criticism with its commercial effect, intellectual impact and archiving function is crucial to theatre and therefore suggests that theatres, arts organisations, and even the Arts Council England should sponsor theatre criticism. However, as Lyn Gardner pointed out in her rebuttal to Orr's arguments, there have only ever been about ten to fifteen critics making anything approaching living by writing about theatre in the UK.

But, ten to 15 is still a considerably better number than "zero". And, currently newspapers are pretty much the only places paying anything approaching the sort of money for criticism needed to live on. (This situation is exacerbated by the fact that nearly all critics feel the need to live in London, because such a ridiculously high percentage of the country's theatres are located there. And since London is also one of the most expensive cities in the world, they need more money to afford to be able to stay there.)

How will criticism survive? And how is it going to be funded?

Of course, newspaper criticism – whether in print or online – may survive in some form. Probably with fewer jobs and with an increasingly lower quality of writer. It is worth also noting that while British critics have never trained, or often even studied a related discipline, there has been a trend in recent years for editors to appoint either middlebrow celebrities or simply journalists who shared their (right-wing) political opinions. This has done infinitely more damage to the label of "professional critic" than any blog ever could.

Andrew Haydon is writing about German theatre

Andrew Haydon is writing about German theatre

on his blog, too.If we want serious, popular theatre criticism in the UK, like I believe you have in Germany – on this site (which pays contributors), or in Theater Heute and Theater der Zeit – we have to establish where and how it is going to be found and how it is going to be funded.

Improve or decline

How urgent this need is is hard to assess. Orr asserts that the current picture – of young, truly first-class writers about theatre, all writing unpaid in return for free theatre tickets – is unsustainable. And it's true that if we want to see this current generation continue writing about theatre until they retire, we're going to need either new funding models, or a serious change in the intellectual culture of our newspapers. On the other hand, perhaps there will never be a shortage of talented young people who care passionately about theatre and write brilliantly about it. And perhaps the career path of the young critic in the future won't be to carry on in the same job forever, but might, like Britain's most revered post-war critic, Kenneth Tynan, only involve ten-years writing criticism before moving on to literary management or dramaturgy.

But, while we're in the grip of a recession, it is easy to submit to crisis-thinking. The situation could just as well improve as decline. Twenty years ago there was a "crisis of new writing" in Britain. Now, after the emergence of Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill and Martin Crimp (to name but three) in the nineties, and of Simon Stephens, Dennis Kelly and countless others in the last decade, that's just about the last aspect of our theatre "in crisis". Obviously we can't see the future, but that doesn't mean we have to face it with fear rather than optimism.

Theatre-Blogs – six of the best:

Maddy Costa – statesofdeliquescence.blogspot.co.uk – Co-founder of the "Dialogue"-Project with Jake Orr, professional print-media critic turned online theatre-writng activist, Costa's writing not only pushes hard at the accepted boundaries of how reviews are written, but also invests significant time in nurturing young critics.

Exeunt Magazine – exeuntmagazine.com – Edited by Natasha Tripney, Daniel B Yates and Diana Damian, Exeunt has become the de facto home for the best theatre writing being practised in the UK today. Stand-out critics, apart from those mentioned below, include all three editors, Stewart Pringle and Tom Wicker.

Chris Goode – beescope.blogspot.co.uk – Currently closed to new entries but a six year archive by the genius writer, director and performer Chris Goode, whose blog absolutely led the way in writing about theatre, both as a maker and a watcher. Set the high water-mark for UK theatre-blogging.

Dan Hutton – danhutton.wordpress.com – one of the youngest, and without doubt most perceptive online critics, Hutton's youth, his socialism, and and his critical acuity make him the most likely contender for the title of "The Next Kenneth Tynan".

Catherine Love – catherinelove.co.uk – Writing with perhaps the most statesmanlike poise, grace and diplomacy of all the online critics, Love has made a name for herself by writing about the most contentious shows and theatre scandals in a way that no one can argue with.

Matt Trueman – matttrueman.co.uk – Theatre-blogging's most conspicuous mainstream crossover success, Trueman started out as a critic for the theatre section of CultureWars (then edited by Andrew Haydon) while working as a actors' agent, and rapidly became one of the most prolific freelance contributors to the mainstream/print media.

Andrew Haydon – postcardsgods.blogspot.co.uk – "One of the most brilliantly thoughtful, perceptive and in every good way irritating critics de nos jours. He's not only written with a near-perfect balance of analytical acuity and sozzled lyricism about the most interesting theatre in Britain and on the continent, he's also come to stand for an absolutely crucial agenda around how and why we view theatre in this country, both as audiences and as makers." (Chris Goode)

Switch to the German translation.

All English texts on nachtkritik.de are listed here.

Andrew Haydon used to work as a freelance UK theatre critic (Financial Times, Guardian, Time Out, etc.). He was also the editor of the CultureWars theatre section between 2000-2010, where he discovered exciting new theatre thinkers, including Andy Field, Matt Trueman and Miriam Gillinson. His account of British theatre in the 2000s is published by Methuen in Decades – Modern British Playwriting: 2000-2009 (ed. Dan Rebellato). His Blog: postcardsgods.blogspot.co.uk

Andrew Haydon used to work as a freelance UK theatre critic (Financial Times, Guardian, Time Out, etc.). He was also the editor of the CultureWars theatre section between 2000-2010, where he discovered exciting new theatre thinkers, including Andy Field, Matt Trueman and Miriam Gillinson. His account of British theatre in the 2000s is published by Methuen in Decades – Modern British Playwriting: 2000-2009 (ed. Dan Rebellato). His Blog: postcardsgods.blogspot.co.uk

Wir bieten profunden Theaterjournalismus

Wir sprechen in Interviews und Podcasts mit wichtigen Akteur:innen. Wir begleiten viele Themen meinungsstark, langfristig und ausführlich. Das ist aufwändig und kostenintensiv, aber für uns unverzichtbar. Tragen Sie mit Ihrem Beitrag zur Qualität und Vielseitigkeit von nachtkritik.de bei.

mehr debatten

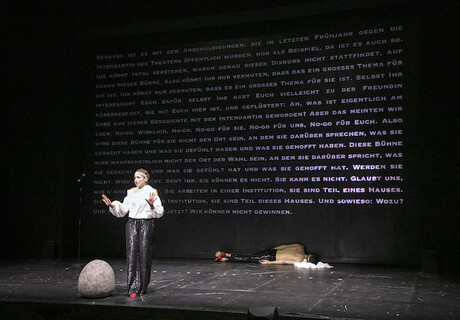

- Theatre criticism UK: Kinder- und Jugendtheater

- #1

- KJT-Freundin

meldungen >

- 15. April 2024 Würzburger Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

- 13. April 2024 Braunschweig: Das LOT-Theater stellt Betrieb ein

- 13. April 2024 Theater Hagen: Neuer Intendant ernannt

- 12. April 2024 Landesbühnentage laufen 2024 erstmals dezentral

- 12. April 2024 Neuauflage der Demokratie-Initiative "Die Vielen"

- 12. April 2024 Schauspieler Eckart Dux gestorben

- 12. April 2024 Karlsruhe: Graf-Hauber wird Kaufmännischer Intendant

neueste kommentare >

-

Rücktritt Würzburg Nachtrag

-

Leser*innenkritik Anne-Marie die Schönheit, Berlin

-

Erpresso Macchiato, Basel Geklont statt gekonnt

-

Erpresso Macchiato, Basel Unverständlich

-

Leserkritik La Cage aux Folles, Berlin

-

Medienschau Arbeitsstelle Brecht Ein Witz?

-

Landesbühnentage Kleinmut

-

Kolumne Wolf Autorenvereinigungen

-

Erpresso Macchiato, Basel Transparent und freundlich

-

Leserkritik Cabaret, SHL Flensburg