Debate about the Future of Germany's City Theatres XVII - We must hold on to our old texts by letting them go, says Alexander Kerlin, Dramaturg at Theatre Dortmund

The Debris of Modernism

by Alexander Kerlin

Dortmund, October 16, 2014. Must we rebuild theatre from scratch? Matthias Weigel's suggestion to reset the theatre's identity and reputation using "pools and party", made last week as part of his article "Tear Down the Walls of Tradition", must likely be taken with a grain of salt. And yet, he does recommend the theatre sever ties with a particular part of its history – or at least distance itself from it.

The Wounded Might of the Canon

If I'm to understand correctly, this part of history consists primarily of the so-called "classics" – the great stories, the big (and smaller) ideas of the 16th (England), 17th (France), and 18th (Germany) centuries, as well as the tragedies of ancient Greece. Weigel's suggestion comes at a time – and likely not coincidentally so – when our supply of history is already waning, as one of the many consequences of the digital revolution. On the Internet, messages reach us independently of their objective importance constantly, abundantly, and in real time.

Dominion of old texts?

Dominion of old texts?

Therein lies my first proposition: the "classics" qualify as a type of ammunition to defend our lives against Apple's, Google's, Facebook's, Twitter's, and Amazon's attack of the Now. That said, Weigel is correct when he implicitly doubts whether the "classics", in the absence of their radical alteration, can still "mean something" to us today. Every sensitive inhabitant of the 21st century has likely sensed this conundrum in the theatre before. My second proposition, then, which could also be considered an effect of the digital revolution, is that the Internet has long broken the reign of the canon. This paradox is the subject of the following essay: We no longer have use for the classics, but we need them. So what are we going to do with them?

The idea of the erasable identity of the theatre and a longing for "neutrality", even if meant well (re: "diverse audiences"), are problematic. Weigel's call for a D-Day in the theatre is indicative of the ideological flipside of what he calls the "dominion of old texts". In this model exists either the dominion of old texts, or their abolishment. Weigel's essay itself is more complicated and conflicted than that, but the idea of the final "cleansing" of the theatre from its history is only one mental step away – which is evermore striking in light of the fact that our persistent celebrations of the Now seem to be developing into a distinctive signifier of the digital age.

The City Theatre as "Cloud"

In this context, the author Douglas Rushkoff has recently coined the phrase "present shock": when everything happens Now and is available in real time, without filters – world politics, the neighbour’s vacation photos, soccer, decapitation videos, rehearsal impressions on theatre blogs, friend requests, and sexual promises – people become paralyzed and are kept in a state of constant alertness. What’s gradually lost in this process is the past (the Other of the Now), from which we could draw the terms and models necessary to recognize the present shock and comprehend and describe it as a mechanism of control over humans and entire systems.

Weigel’s essay touches on the digital revolution only peripherally. This is peculiar, as his visionary model for the theatre contains patterns of thought and perception that (though older than the Internet) fully unfold only in daily interaction with the internet. According to Weigel, productions, seasons – essentially everything that takes place within the architecture of a city theatre – should rhizomatically, like a cloud, sprawl around issues, ideas, and even around "a movement, a feeling" – much like during a walk through the internet – as part of the collective work of multi-tasking, cross-media savvy subjects.

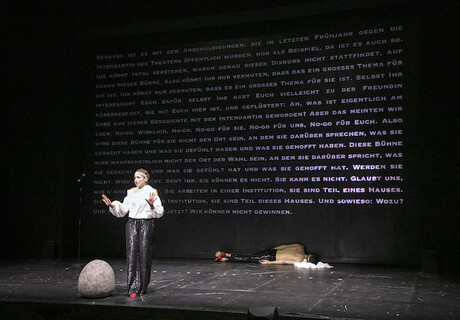

Reading the programme afterwards to find out what you've seen?

Reading the programme afterwards to find out what you've seen?

To avoid any misunderstandings: I generally share this vision. Attempting its realization comprises my daily work as a dramaturg. I work with directors, actors, and playwrights, just as much as with programmers, street artists, activists, independent theatre groups, media artists, nerds and freaks, researchers, performers, film makers, bloggers, interior designers, musicians, and "laymen" of all ages. The wooden stage comprises only one of the stages on which theatre makers of the future will create work. The internet, mass media, and public space will become equally important stages for the essential interplay between fiction, reality, and the grey areas in between.

I share Weigel's analysis of outdated training opportunities for actors, but would also add those for dramaturgs, directors, writers, and performers. Germany lacks a theatre school that teaches physical-vocal work and acting training in conjunction with a theory-based practice – a model we know from the universities in Giessen (Applied Theatre Studies) and Bochum (Scenic Research). (At Yoram Loewenstein’s Performing Arts Studio in Tel Aviv, acting and directing students must spend six months working in the neighbourhood's refugee families before they may tread the boards of the stage for the first time. Not a bad idea, either.) I also share Weigel’s resistance towards arrogant theatre makers who have no confidence in their audiences, who avoid topics, issues, or experiments in form, because "no one here gets it", or because people might feel "attacked".

Eroded Foundation

Nonetheless: a contemporary theatre requires critics who don't simply demand its historical cleansing for the benefit of an overabundance of the Now ("Ukraine, Syria, and Gaza"), but those who develop an affinity for considering the epistemes of the times and incorporate them into their analyses. More concretely, this means that the medium has yet to become the message. Of importance in the theatre is not merely the topic of new wars; more crucial is how new wars are communicated – how the journalistic story itself is blasted open by the new medium, along with its subjects' entire inner orientation and concept of self. In his 2008 book Studies about the Next Society, the sociologist Dirk Baecker categorized the new era – the conquest of computer and Internet — alongside the major epochal shifts that followed the invention of language, writing, and the printing press. In the same way as the digitalization has cut people and institutions off from their modern and post-modern histories, causing them to drift and lift off, the "next society" is fundamentally eroded, lastingly changed in thought, feeling, work, and perception.

Struggle for Survival without a Victor? Screenshot of the Computergame "This War of mine"

Struggle for Survival without a Victor? Screenshot of the Computergame "This War of mine"

Source: 11 Bit Studios

The epochal shift of the next society does not simply represent a discontinuity along the axis of time, but rather a challenge of the axis itself as a plausible representation of time. The Internet communicates the simultaneity of events, rather than their linear progression within a scheme of past, present, and future. It communicates their expansion horizontally, rather than as a vertical plunge into the deep well of history. The Internet is not a place from which five-act dramas emerge. That is not to say that the axis of time is to disappear completely. Rather, today, different concepts and regimes of time exist in conflict with each other.

Our backwards gaze into the old century seems increasingly warped. It’s becoming more and more difficult to comprehend what exactly was on people's mind prior to the digitalization, what they aimed for in their stories and non-stories, how they produced and consumed sense and non-sense. Beneath the heavy steps of the actors, the creaking of the wooden stage tends to sound more like the echo of a lost era, and less like a soundtrack for our contemporary lives that could possibly provide guidance in our overwhelmingly demanding world.

Mantras of Intellectual Laziness

The wooden stage and its fluffy seats no longer suffice to still our hunger for alternative thought and life, for transformative artistic experiences, and for a true counter public. In this regard, Weigel’s analysis hits the nail on the head. It is becoming increasingly clear that Shakespeare, Moliere, Lessing, Schiller, Brecht, Beckett, and Bernhard, told and retold in one of the many variations of the proscenium arch, don’t have much to say to us about ourselves anymore, nor about the basic features and problems of this era. The more "clever" or "youthful" a production is, the less applicable it is to us.

Weigel rightly suggests that "every old story is likely to contain a point that one could consider a metaphor for the current state of affairs." But who today is satisfied by metaphors? It is intellectual laziness on the part of theatre makers, as well as an insult to their audiences’ intellects, to claim that one could easily illuminate 21st century questions of power and control simply by way of retelling a baroque story about a king. Nobody gets that. These two issues don’t resemble each other, not even from a distance. Queen Elizabeth is not the same as Angela Merkel. The claim to "archetypes", to "timeless, human types of conflict” is the enduring mantra of this intellectual laziness. Quite a while ago yet, Rene Pollesch asked why so many plays at the theatre consistently require us to read the programme afterwards – to understand what we’ve seen and what problems and conflicts were being treated – when one could just as well transfer the programmes onto the stage, using them as dialogue and scenic material instead.

This once again illustrates the crucial paradox that theatre makers and critics should seriously consider: First, the classics mean increasingly less to us. The demise of the bourgeois canon has already begun; the Internet has broken its reign. Secondly, the characteristic attribute of the digital age is a fetish of the Now, which has set off a suppression of the past like we've never seen before. If we wish to avoid the manure and mud of the past century welling out from underneath us – and endangering us – we must figure out how to bequeath the next society our cultural heritage by passing it across the epochal shift of the digital revolution.

Landscapes of the Next Society

Gustav Mahler's famous phrase, "Tradition is not the worship of ashes but the preservation of fire", at least contains the word "preservation". To induce a type of tabula rasa, to literally "neutralize" the history of the theatre, to proclaim zero hour, because one can’t stand the melodrama anymore, because one no longer wants anything to do with one’s own history and because that history allegedly scares away newcomers who don’t like history or who have a different history or who would rather go party anyway, is a bad idea. Not just because the repressed always return – with a dreadful grimace at that – but also because we desperately need the mountain of material that modernism has built and left for us: as a giant storehouse of thought, feeling, perception, and action. New forms of artistic freedom will require us to use the debris of modernism and postmodernism to build new, temporary houses in the landscapes of the next society, on those stretches of land above which the fog is just beginning to lift.

Arrival at the Next Society? Screenshot of the Computergame "Skyrim". Source: Bethesda

Arrival at the Next Society? Screenshot of the Computergame "Skyrim". Source: Bethesda

We must hold on to our old texts by letting them go. First, they must be torn off their pedestals, and grabbed from the hands of guardians of public virtue – bourgeois intellectuals, second-class language and literature professors, and all those who harbour romantic memories of their first Faust encounters. The texts must be emancipated from their sanctifications by preachers of the cult of genius (heirs and publishers) and the meekness of their altar boys and girls (dramaturgs). Surely, Tennessee Williams has written a few nice plays, but none of them even begin to compare to the storytelling prowess of TV shows like The Wire or Breaking Bad. How is it possible that the German legal representatives of Williams’ heirs cause a fuss about his plays as though they comprise direct messages from god? How is it possible that grown adults with university degrees fight jealously over interpretive authority like children over a plastic toy? In current times, countless art works of immense quality are created at the intersections of TV, internet, and media art – so much so that our theatres will soon find themselves wondering who really has a monopoly on high art today.

Secondly, the time of "updating" classics is over. From now on, these texts no longer exist to simply be staged in contemporary clothing, to be "newly interpreted". Their productions will no longer be peppered arbitrarily with projections of contemporary politicians. Instead, theatre makers of the future will recoil at such symbolic means of representation, which serve no other purpose than to suppress and cover up the question of "what's the point of all of this"?

Risking Ruptures and Discontinuities

The greatest ball and chain in our practical work with the classics is the dominion of narration, that is, the rigidity of form, which privileges a story’s overall arc over its constituents – its "moments". Rehearsal processes and especially performances are remarkably constrained and limited, if single moments are constantly transcended – degraded – for the benefit of that which the moment lacks –"the whole". We need dramaturgs who are willing to risk radical adaptations, who are more invested in difficult questions than in characters’ arcs, who are interested in constellations of seeing and being seen, in perspective, redundancies, and technique, in musical, rhythmic, philosophical and sociological questions, in motifs and word clusters – with an eagerness to expand texts horizontally.

In these textual landscapes, theatre makers must combine texts from various sources, intelligently and richly contrasted, using techniques we know from music and visual art, such as mash-up, looping, and remixing. They must be able to tell stories backwards, forwards, and starting in the middle. They must risk lengthy stretches and extensive repetitions. They must include technology in their dramaturgical conceptions, and consider it equal in importance to the text; that is, they must be able to imagine the "how" (form) and the "what" (content) united in a single gestalt. They must experiment with digital technology, and in doing so never cease to question the "why" of its usage in relation to content. Never employ technology just because you can. We need theatre makers who, aside from the 'round arc', are also interested in discontinuity and rupture, in illogic and tangents; who enjoy excess just as much as reduction; who find as much pleasure in a string of miniature narratives as in sketching a grand story. Who know that time can pass along circles and spirals just as well as it can along a line with a beginning and an end. Who master "authentic play" as much as "speaking in quotes".

Yes, citation. Throughout this our current epochal shift, accessing the classics will become a process of citation rather than of holistic appropriation. Take Samuel Beckett, for example, whose copyright representatives have posed as particularly humourless in the past few centuries. We no longer need Beckett’s Waiting for Godot as a readymade package – a pretty parcel for which one must audition meekly before the publisher.

Instead we will quote Beckett’s brilliant thoughts in accordance with the right to citation, as miniatures in our collages. They belong to all of us. To take and relocate them is part of our future artistic freedom, which has already commenced. And the crystalline beauty of those fragments of text, their radicalism and endurance, will thus be revealed again, as weapons of thought and feeling. Freed from the stench of wholesome narration, they will become balm for our Now-infested souls.

(Translation: Fannina Waubert de Puiseau)

All English texts on nachtkritik.de are listed here.

Alexander Kerlin (*1980) is a dramaturg and playwright and has been in residence at Theater Dortmund since 2010. There he founded the Dortmund speaking choir and received particular attention for his work with Kay Voges (Dogma 20_13: Das Fest based on Thomas Winterberg and Das Goldene Zeitalter – 100 Wege dem Schicksal die Show zu stehlen). He is currently working on an adaptation of Elektra for the Theatre Dortmund, and is writing and sampling for the upcoming productions of Kaspar Hauser und die Sprachlosen von Devil County and The Madhouse of Ypsilantis (2015).

Alexander Kerlin (*1980) is a dramaturg and playwright and has been in residence at Theater Dortmund since 2010. There he founded the Dortmund speaking choir and received particular attention for his work with Kay Voges (Dogma 20_13: Das Fest based on Thomas Winterberg and Das Goldene Zeitalter – 100 Wege dem Schicksal die Show zu stehlen). He is currently working on an adaptation of Elektra for the Theatre Dortmund, and is writing and sampling for the upcoming productions of Kaspar Hauser und die Sprachlosen von Devil County and The Madhouse of Ypsilantis (2015).

The German version of Kerlin's Text can be found here.

Other English texts on nachtkritik.de:

- The Social Pressure of Conformity – Jacob Appelbaum's opening speech for Theater der Welt 2014

- Crisis, what crisis? – a debate on theatre criticism and its crisis in the UK

- Playing Democracy – Christian Rakow about the New Game-Theatre and its political relevance

Wir bieten profunden Theaterjournalismus

Wir sprechen in Interviews und Podcasts mit wichtigen Akteur:innen. Wir begleiten viele Themen meinungsstark, langfristig und ausführlich. Das ist aufwändig und kostenintensiv, aber für uns unverzichtbar. Tragen Sie mit Ihrem Beitrag zur Qualität und Vielseitigkeit von nachtkritik.de bei.