Festival Theaterformen 2018 "Watch & Write" - Enos Nyamor on Kenyan Theater today

Braunschweig, 10. Juni 2018

Finding New Meanings of Performance Spaces

by Enos Nyamor

Kenyan Theater has been in neglect for years. But has it ever existed? A description of colonial and postcolonial influences on performance spaces.

The greatest obsession of this century is, perhaps, the intersection between space and time. Topics of diversity, of cultural exchange, and of migration and globalization dominate contemporary narratives. These elements of our post-modern time, for Kenya, as well as most former colonies, are shrouded in the mist of imperial legacies.

Nowhere else is this quality evident than in the nature of performance spaces in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital. What is today the East African state’s main theater, The Kenya National Theatre, was built in the 1950s, at the height of the independence struggles. During the colonial period, this space was almost inaccessible to Africans, and hosted shows that premiered in Europe, for Europeans on safari and also for the amusement of the settlers. The transition from colonial to self-rule have, somehow, seamlessly overcome the connection between space and time, transposing meanings from the past to the present.

Entrance to Kenya National Theatre. The lounge bar can also be seen at the balcony atop the entrance

Entrance to Kenya National Theatre. The lounge bar can also be seen at the balcony atop the entrance

© Thomas Rajula

“[The] true meaning of this space lies in the collective aspiration of the people, and not in the structure. Demolishing the building does not necessarily suggest new meanings,” says Alacoque Ntome, a theater technician at the Kenya National Theatre.

Beside the National Theatre there are some alternative performance spaces. The Phoenix Theatre is the most prominent out of them. Although it was a vibrant performance space in the 1980s and 1990s, it faced dwindling membership, until the space was seized on account of outstanding arrears in 2017. James Falkland, who founded the Phoenix Theatre in the 1980s, has before been the last European administrator at the Kenya Cultural Center. In the 1970s, a wave of Africanization programs had displaced sediments of colonial administrators including Theater directors.

The Theaters are located in affluent areas

Like the Kenya National Theatre, the Phoenix Theatre was situated in an affluent location, only a few meters from the national parliament buildings. After its closure in 2017, Mugambi Nthiga, a member of the defunct Phoenix Theatre Players, observed that the location had inspired apathy, leading to a fall in revenue. In the 1990s, during its heydays, the Phoenix Theatre staged a new play each month, and thrived under James Falkland’s administrative talents. Some of Kenya’s gifted actors, including Lupita Nyong’o, nurtured their skills at the Phoenix. Moreover, during that period, the Phoenix Theatre was the main alternative to the national theater, especially as it faced neglect in the 1980s and 1990s under President Daniel Moi’s rule.

“At some point, before performing, Theater Companies had to seek permission from the special branch,” says Alacoque. The special branch was the repressive secret police that existed in Kenia until 2002.

© www.nairobinow.files.wordpress.com

© www.nairobinow.files.wordpress.com

Even so, in the last decade, the number of theaters in Nairobi have shrunk significantly. Some institutions, such as the French Cultural Center and the Goethe-Insitut, offer alternative performance spaces for theater companies. For instance, the French Cultural Center provides its auditorium at subsidized local rates. The French cultural center works with a handful of theater companies, mainly because of the long term relationship with these groups.

“Our space is open to any production company, as long as they conform to our policies on non-religious and non-political content,” says Harsita Water, the cultural program manager at the French Cultural Center.

The National Theater is never sold out

In a nation where most residents live on less than two euros in a day, the ticket fees of between four and ten euros can deny many access to the spaces. Interestingly, the Kenya National Theatre, with a capacity of 375, barely attracts a full house. Because theater companies must be profitable to remain operational, ticket pricing can, ostensibly, alienate low income earners.

“I believe that it is possible to make costs as affordable as possible, and even increase accessibility, by performing at least three shows in a day,” Harsita says. “But that is to the discretion of the respective theater companies.”

Heavily armed paramilitary in front of the Theater

As part of the celebration of fifty years of self-rule, the Kenyan government, in collaboration with Kenya’s leading brewer, funded the renovation of the Kenya National Theater. The primary cost of the renovation was the reduction of the capacity from 475 to 375, specifically because of the changes in seat arrangements and design.

For some emerging artists, the compound at the Kenya Cultural Center, of which the national theater is part, was a place of unfettered freedom. However, after the renovation, the space has been gradually becoming more restrictive. The compound is marked by presence of heavily armed paramilitary.

“The officers began patrolling the compound after artists had repeatedly committed illegalities. They attacked a guard. And that’s when the administration invited the police to extend the patrols within the compound,” Alacoque tells the writer.

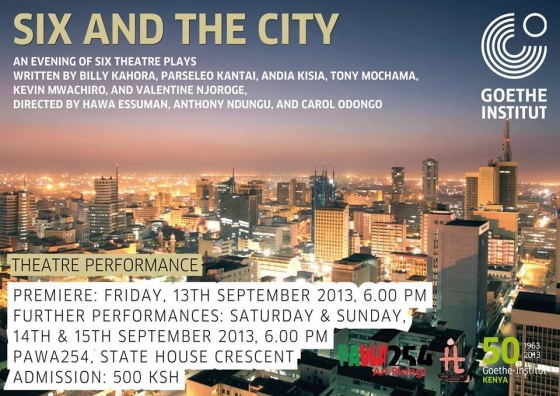

2015: Secretary of State John Kerry meets Boniface Mwangi im PAWA 254 © www.nairobiwire.comWhile independent theater companies have been on the rise, most of these groups are limited to access to permanent spaces. The revolutionary Pawa 254, with its iconic rooftop stage, have provided actors and spoken word artists with platforms for expression. One of Kenya’s most outspoken activists, Boniface Mwangi, founded this space in 2011, and it has become a hub of resistance art.

2015: Secretary of State John Kerry meets Boniface Mwangi im PAWA 254 © www.nairobiwire.comWhile independent theater companies have been on the rise, most of these groups are limited to access to permanent spaces. The revolutionary Pawa 254, with its iconic rooftop stage, have provided actors and spoken word artists with platforms for expression. One of Kenya’s most outspoken activists, Boniface Mwangi, founded this space in 2011, and it has become a hub of resistance art.

Besides, in Kenya, television and film overshadow theater. The decrease in corporate sponsorship, dwindling ticket sales, and censorship, have undermined theater evolution in Kenya in general, and Nairobi in particular.

Nevertheless, deeply entangled in the post-colonial narrative is the idea of labelling, sanctifying, and appropriating formerly exotic spaces to represent part of a national culture. Indubitably, theater and performance spaces in Nairobi are yet to achieve the democratization that, in the end, would transform them into heterotopias, into spaces that radically differ from and inspire sites around them.

Enos Nyamor is a cultural journalist based in Nairobi. His writings have appeared on C&, Sunday Nation, and Business Daily Africa. A student from the C& Critical Writing Workshop, which was held in Nairobi in December 2016 and made possible by the support of the Ford Foundation, Enos has been writing about art from 2013 on.

Enos Nyamor is a cultural journalist based in Nairobi. His writings have appeared on C&, Sunday Nation, and Business Daily Africa. A student from the C& Critical Writing Workshop, which was held in Nairobi in December 2016 and made possible by the support of the Ford Foundation, Enos has been writing about art from 2013 on.

Hier die deutsche Übersetzung dieses Artikels.

Here Milisuthando Bongela writes about the situation of cultural journalism on the African continent. And here Yvon Edoumou on the question whether "poor" people can enjoy arts. Stéphanie Dongmo portraits the theatre director Martin Ambara from Cameroon (in German).

This text is a product of "Theaterformen" festival's journalistic project "Watch & Write" and is being published on nachtkritik.de in the context of a media cooperation with the festival. It is not part of the regular programme on nachtkritik.de.

Schön, dass Sie diesen Text gelesen haben

Unsere Kritiken sind für alle kostenlos. Aber Theaterkritik kostet Geld. Unterstützen Sie uns mit Ihrem Beitrag, damit wir weiter für Sie schreiben können.

mehr nachtkritiken

meldungen >

- 24. April 2024 Deutscher Tanzpreis 2024 für Sasha Waltz

- 24. April 2024 O.E.-Hasse-Preis 2024 an Antonia Siems

- 23. April 2024 Darmstadt: Neuer Leiter für Schauspielsparte

- 22. April 2024 Weimar: Intendanz-Trio leitet ab 2025 das Nationaltheater

- 22. April 2024 Jens Harzer wechselt 2025 nach Berlin

- 21. April 2024 Grabbe-Förderpreis an Henriette Seier

- 17. April 2024 Autor und Regisseur René Pollesch in Berlin beigesetzt

- 17. April 2024 London: Die Sieger der Olivier Awards 2024

neueste kommentare >