Festival Theaterformen "Watch & Write" - Ayodeji Rotinwa writes a letter about Milo Rau's "Compassion. The History of the Machine Gun"

June 17th, 2018

Pity At What Price?

by Ayodeji Rotinwa

Dear Timehin,

I am writing to you with fatigue.

As you know, I am in Braunschweig attending a workshop set within the town’s major art calendar event, Festival Theaterformen. I have seen more plays here than I have in my entire life, in an amount of days I have lost count of. I am enjoying the experience but worry I’m getting too tired to appreciate all of it. I am taking solace in following what’s new with you on Instagram. It appears you have found love while I have been in a hopeless place.

Anyway, I saw something I felt I must share with you and we can discuss when I return. A play by a celebrated (here, at least) Swiss theatre director, Milo Rau.

There is a lot to pity in the play

In English it was called Compassion. The history of the machine gun. I have seen it called "Pity" elsewhere in German, online. It appears I cannot trust Google German translations. I prefer the second name. There is a lot to pity in the play, indeed.

Before I start, I must mention that this play is not meant for you or me. But it is a story about you and me, or perhaps more specifically, people like you and me. It tells the story of our ‘neighbours’ in Congo, if they may be called that by virtue of the fact they are also African but it is meant for a European audience. It was meant to unsettle them, shock, even prickle their conscience. It did not do any of those things, for me. According to my friend Wolfram, plays like this aren’t often made or shown here in Germany. I was not surprised. I only recently learned that colonial history isn’t taught in German schools either. You would think over a century of territorial conquests, oppression, control which resulted in a dramatic turn in fortunes for them, would be worthy of an inclusion in their curriculum. The 1884 conference that set all of these off, that marked and divided African people, families, cultures, histories, sowed seeds of conflict, friction was made in Berlin after all.

Europaen guilt trough the eyes of a NGO worker

Anyway, back to the play, it questions white, European guilt and involvement in conflicts and the resulting effects in Congo, in Rwanda and elsewhere in Africa – through the eyes of a NGO worker played by Ursina Lardi and Consolate Siperious, an actress and genocide survivor. Siperious tells us, while on stage but speaking into a screen, shown overhead that her parents killed, lived through wars in Burundi and was adopted, (acquired I might even say) by a Belgian couple intoxicated by news from our supposedly, exclusively dark, poor, exotic continent. I suppose they might have changed their minds if they knew we were not a people who needed helping, but to be left alone. Surely, they don’t know that some of the artefacts of stupendous value sitting in European museums were stolen from Africa? Or the cobalt that powers their iPhones? Who is helping who? But I simplistically digress.

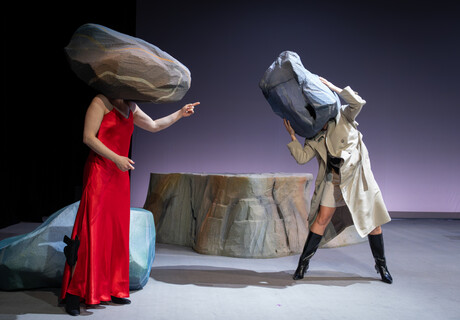

© Daniel Seiffert

© Daniel Seiffert

The play also asks why one crisis is given attention over the other. No one in the mostly white audience likely knew for sure whether it was five or six million people who died in the genocides in East Africa. For a people so good at preserving buildings and monuments, Timehin, you might expect they would know better. Ursina Lardi, apparently playing herself certainly doesn’t know about things like this. She only found out about Aylan Kurdi - the unintended face of the refugee crisis in Eurasia - when her director showed her a picture of his lifeless body on a Turkish beach.

Humanitarian aid and arms

The play also interrogates white compassion, how Europeans flock to these crisis hotspots, to help while simultaneously fuelling them with arms and pitting people against themselves over profit off natural resources, and benefitting from same. This is where the real meat of the play is. Ursina, wearing a blue dress, with blond hair and blue eyes reminiscent of the European Union flag, goes to Congo to save it as most young, white people do, as a rite of passage, a checklist of compassion to be fulfilled. She describes and objectifies black bodies there, calls them Giacometti figures. She says she would stroke black children like she would animals. She recalls scenes of murders, rapes, refugee camps, warlords. She may have left out tropical diseases. I’m not sure. She does so while marooned in filth on the stage: tattered clothes, broken furniture, foliage, machine guns. It was unclear if this was supposed to be a metaphor for Congo.

Consolate sits on stage facing a screen while Ursina does most of the speaking. We only hear her at the beginning and end. This is part of the point as well I suppose, that someone other than African tells a story like this about us in the name of helping. Timehin, as you know, it is the United Kingdom’s DFID who tells us how many women are out of work in North-East Nigeria and so therefore need to be economically rescued, post haste. It is Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that tells us when polio comes or goes.

The cost of the play is unbearable

The play’s aims, while somewhat appreciable comes at a cost that I find unbearable. I have been thinking about it the past few days and I have wondered, questioned myself, if I am overreacting or being too sensitive. I’d like to know what you think when we see.

To my mind, in order to criticise white curiosity, guilt, extent of compassion, the director Rau, reproduces African suffering in the well-oiled, well-documented medium of a single story. You do remember the term right, made popular by our favourite author Chimamanda Adichie. Not that you need reminding but the danger of a single story is that it creates stereotypes. As Adichie said, "the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but they are incomplete.” It is interesting to note that Rau has a history of this.

Do you really nead Congolese suffering to talk about white guilt?

In 2017, he made a theater play, Congo Tribunal, about the injustices of wars in Congo, created a fictional tribunal to judge same, using ‘’real’’ performers who had to relive their suffering and pain of the war, for authenticity I suppose, for his production. In 2011, he created Hate Radio, a play and reenactment of how a radio station contributed in inciting the Rwandan genocide with actors rehashing inflammatory - to say the least - statements in piercing detail.

Is there really no other original way to confront the topic of white guilt, complicity questionable compassion without Congolese suffering as fodder? Did you know that the some of the arms that are fuelling most conflicts in Central Africa, come directly from Europe, are traded for diamonds, oil?

Apparently, Rau does not care for the rigour of interrogating these details, Timehin.

Eventually, we hear Consolate’s voice again. In exaggerated telling, where her face, nose, eyebrows are moving as much as her lips are, she reports details on the genocide again. People not being buried. Bodies going missing. She might as well have been telling a story about pigs flying. Ursina, the problematic white saviour has left the stage by now.

At play’s end, the people who had hopefully learnt the limits of their compassion, burst into lengthy applause.

A pity, indeed.

Ayodeji Rotinwa is a freelance writer and critic who covers art & culture, social justice, sustainable development and often, how the latter two intersect with the first. Passionate about arts administration, he was in the (communications) team that managed Nigeria’s debut pavilion at the Venice Arte Biennale, known as the "Olympics of visual art.” He has been published by Financial Times, Art Forum, Roads & Kingdoms, amongst others.

Ayodeji Rotinwa is a freelance writer and critic who covers art & culture, social justice, sustainable development and often, how the latter two intersect with the first. Passionate about arts administration, he was in the (communications) team that managed Nigeria’s debut pavilion at the Venice Arte Biennale, known as the "Olympics of visual art.” He has been published by Financial Times, Art Forum, Roads & Kingdoms, amongst others.

See the German version of the text

Here Milisuthando Bongela writes about the situation of cultural journalism on the African continent. Yvon Edoumou questions whether art in Kinshasa is accessible for "poor" people. Stéphanie Dongmo portraits the theatre director Martin Ambara from Cameroon (in German). Ismael Fayed writes about the production "Saigon" by Caroline Guiela Nguyen and Les Hommes Approximatifs. Enos Nyamor reports on Kenyan theatre today, Aboubacar Demba Cissokho covers theatre in Senegal (in German). Carla Lever writes on Cape Town theatres that are challenging South Africa's cultural post-Apartheid segregation. Here Heba El-Sherif on the limitations of Selina Thompson's "Race Cards" and why cultural journalism is important.

This text is a product of "Theaterformen" festival's journalistic project "Watch & Write" and is being published on nachtkritik.de in the context of a media cooperation with the festival. It is not part of the regular programme on nachtkritik.de.

Schön, dass Sie diesen Text gelesen haben

Unsere Kritiken sind für alle kostenlos. Aber Theaterkritik kostet Geld. Unterstützen Sie uns mit Ihrem Beitrag, damit wir weiter für Sie schreiben können.

mehr nachtkritiken

meldungen >

- 15. April 2024 Würzburger Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

- 13. April 2024 Braunschweig: Das LOT-Theater stellt Betrieb ein

- 13. April 2024 Theater Hagen: Neuer Intendant ernannt

- 12. April 2024 Landesbühnentage laufen 2024 erstmals dezentral

- 12. April 2024 Neuauflage der Demokratie-Initiative "Die Vielen"

- 12. April 2024 Schauspieler Eckart Dux gestorben

- 12. April 2024 Karlsruhe: Graf-Hauber wird Kaufmännischer Intendant

neueste kommentare >