Festival Theaterformen "Watch & Write" - Heba El-Sherif on the limitations of Selina Thompson's "Race Cards" and why cultural journalism is important

June 16th, 2018

Becoming the eyes and ears of the masses

by Heba El-Sherif

Last week, I walked out of the inadequate and slightly awkward space at the entrance of the Staatstheater Grosses Haus, where 1.000 questions on race are currently clipped across three walls, with several questions of my own. Beyond the particulars, the show — the most recent version of Selina Thompson’ Race Cards — evokes queries that lie at the intersection of the artists’ proposition, as an artwork concerned with archiving, and the trajectory of critical African cultural writing, a disempowered breed of journalism.

In grappling with the strengths and setbacks of Thompson’ perpetually changing installation, my thoughts have been imbued with questions on the power of artistic and cultural production, and the role of cultural journalists in unpacking this assumed power, insofar as how words can confront limitations such as reach: where the work is exhibited and who will ultimately see it.

The project

In more than a dozen renditions, Thompson has invited audiences to partake in a collective research on racial tension, its origins, and its contemporary manifestations, drawing on her own experience as a black woman in a world where white has been the default, to use the artist’s own words. The installation is composed of 1,000 questions that Thompson came up with in three sittings over 24 hours in Edinburgh. She has since asked viewers from Cornwall to Texas to Toronto, and now Braunschweig to "spend time” with the issues raised and provide at least one answer to a question of their choice. All contributions, including her own, will feed a larger project by the artist.

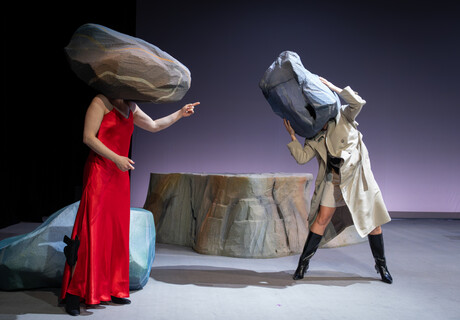

Selina Thompson © Manuel@DARC.media

Selina Thompson © Manuel@DARC.media

Thompson asks her audience about the notion of "exceptional negros,” why dating apps allow racial preference, and if anything good will ever come out of white guilt. She also presses viewers to consider the reasons behind the rise of militancy and question the benefits of non-violent resistance.

The flow is deliberate and at times rhythmic, which makes it easy to take in the questions in one visit. Two consecutive questions on the loss of knowledge prompted this piece: "Why is the work of people of color often erased? How do I stop this from happening to my work?”

Questions

I left the narrow space allocated for Race Cards wondering: why am I asked to think about the perils of racism in ‘a gallery?’ How do we capture the ideas that seep out of its walls, unarticulated? What about our silence? How can we document it? What can we not write? How can one’s bodily responses be archived? Is this a performance? Is it merely a space to get things off our chest, a site of emotional release? Can the act of remembering be a form of healing? If so, how can we record this reconstructive nature of memory? Why was there only one chair in the room?

How does art influence our immediates? Can art ever change the world? Will it affect its course? What about the relationship between art and global power structures: how can art, which is in many ways implicated in the inequalities we face today, participate in shifting paradigms that its content essentially renounces? How can art construct new narratives? Does engaging with "Race Cards" have actual, practical consequences on the legacies of decolonization? In a country where colonial history is not an obligatory subject in school, how can Thompson engage with a generation unable to link its contemporary challenges to a decisive portion of its past? In rewriting history, who holds the power? Are we in need of radically different ways to change people’s minds about racism? And finally, how can society hold a space for all these sentiments, way past the duration of a single show?

Responsibility of cultural journalists

Perhaps one way is to push the conversation outside gallery walls, and therein lies the responsibility of cultural journalists. Art, through its deliberate and unintended consequences, opens up a range of interpretations that give rise to multiple stories about a specific issue, a specific country, or an entire continent. While it might be useful in the context of defining what constitutes good cultural writing to distinguish between reviews, essays and op-eds, ultimately, unpacking the social and political forces from which a specific work of art departs is among the roles of a cultural journalist.

© Andreas Greiner Napp

© Andreas Greiner Napp

In crafting their own reading, journalists become mediators between the work and the audience. They also become the eyes and ears of the masses who do not have access to exhibition rooms, which in the context of most countries in Africa speaks to the battered infrastructures of knowledge sharing and cultural dissemination that have pervaded for decades.

Amid a disinterest in genuine cultural criticism, some have argued for the necessity to make a case for altering preexisting conceptions of cultural journalism, which have rendered it a futile practice across newsrooms worldwide.

My questions on "Race Cards" are born out of a growing interest in working with the archives, nourished by conversations with fellow African writers at Watch & Write. Some of us write in service of cultural preservation, while some are driven by an urgency to correct what has been misrepresented, or recount what has been forcibly silenced. To me, writing about the arts continues to be a strange blend of personal development and responsibility: an eternal seeking of new sources of inspiration fastened by a resolution to take part in telling stories that may otherwise go untold.

See the German version of this text

Here Milisuthando Bongela writes about the situation of cultural journalism on the African continent. Yvon Edoumou questions whether art in Kinshasa is accessible for "poor" people. Stéphanie Dongmo portraits the theatre director Martin Ambara from Cameroon (in German). Ismael Fayed writes about the production "Saigon" by Caroline Guiela Nguyen and Les Hommes Approximatifs. Enos Nyamor reports on Kenyan theatre today, Aboubacar Demba Cissokho covers theatre in Senegal (in German). Carla Lever writes on Cape Town theatres that are challenging South Africa's cultural post-Apartheid segregation. Here Ayodeji Rotinwa writes a letter about Milo Rau's "Compassion. The History of the Machine Gun".

This text is a product of "Theaterformen" festival's journalistic project "Watch & Write" and is being published on nachtkritik.de in the context of a media cooperation with the festival. It is not part of the regular programme on nachtkritik.de.

Schön, dass Sie diesen Text gelesen haben

Unsere Kritiken sind für alle kostenlos. Aber Theaterkritik kostet Geld. Unterstützen Sie uns mit Ihrem Beitrag, damit wir weiter für Sie schreiben können.

mehr nachtkritiken

meldungen >

- 17. April 2024 Autor und Regisseur René Pollesch in Berlin beigesetzt

- 17. April 2024 London: Die Sieger der Olivier Awards 2024

- 17. April 2024 Dresden: Mäzen Bernhard von Loeffelholz verstorben

- 15. April 2024 Würzburg: Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

- 13. April 2024 Braunschweig: LOT-Theater stellt Betrieb ein

- 13. April 2024 Theater Hagen: Neuer Intendant ernannt

- 12. April 2024 Landesbühnentage 2024 erstmals dezentral

neueste kommentare >